In 1988, Alan Moore penned a scathing critique of complacency in the face of fascism known as V for Vendetta. In it, a masked vigilante named V rises to prominence as a direct response to the machinations of a dictatorial regime in '90s England. In 2005, it was turned into a film, where many changes were made to update the setting, the characters, and the message to appeal to a modern (mostly American) audience.

Both the graphic novel and the film chronicle V's selecting and grooming of a protege, Evey Hammond, as well as his mission of revenge against the wrongdoings of a totalitarian government, but they do so in such wildly different ways that a succinct comparison only highlights the varying appeal of both, not necessarily one's superiority. The film still succeeds as one of the most successful comic-to-film adaptations.

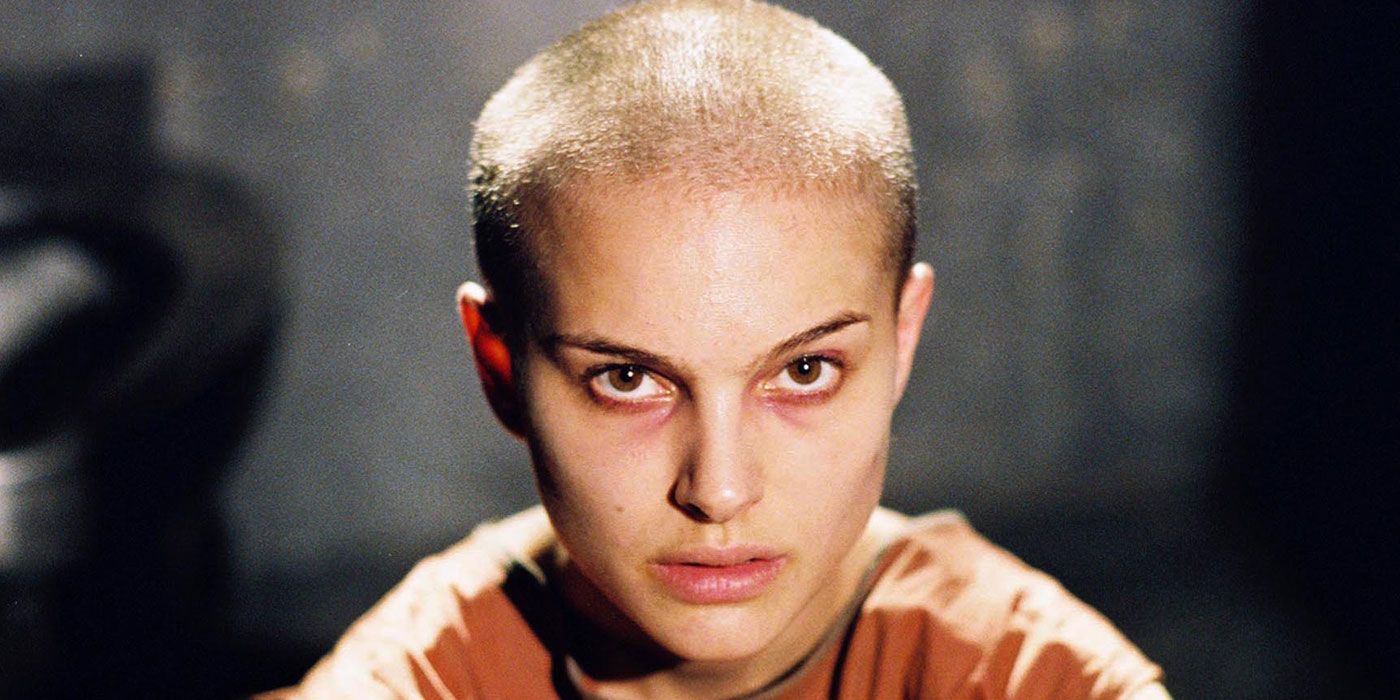

10 BETTER: EVEY'S CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT

In the graphic novel, Alan Moore gives Evey little agency. She's a teenage prostitute with a tragic past surviving by having a romantic relationship with older men like Dietrich, more concerned with scavenging for food than rebelling against a government. She's groomed to be V's replacement and is a background player in his anti-hero's journey.

In the Wachowski film, she's a capable and competent young woman with a decent career, who becomes the hero in her own story towards courageous autonomy after her involvement with V. The film is as much about her as it is about V, and their personalities complement each other.

9 WORSE: CLEARLY DIVIDING GOOD AND EVIL

One of the most salient aspects of Moore's work, whether in V for Vendetta or other series, is his portrayal of classic tropes like "good versus evil" as conceptually grey. The individuals in the Chancellor's Norsefire party truly believe that fascism is saving Britain's population, and V is an unsympathetic anti-hero who kills indiscriminately.

Moore's blurring of the lines between right and wrong when it comes to choosing sides makes the motivations of his characters decidedly problematic. It becomes harder for audiences to relate to a protagonist that is just as easily seen as an antagonist, and very often the villain, which isn't necessarily a bad thing for a more complex story.

8 BETTER: V'S CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT

The anti-hero of the graphic novel is a singularly minded individual consumed by revenge, who doesn't even have a romantic relationship with Evey to make him change his mindset. He does have an impressive vocabulary and flair for the dramatic, but those elements don't give him a fully realized personality.

In the film, V retains his loquacious way with words and gains a love of literature, art, and old Hollywood films. Hugo Weaving imbues V with terrifying ferocity, as well as playful tenderness. While V may represent an idea, he's also a man, no matter how much he tries to deny it.

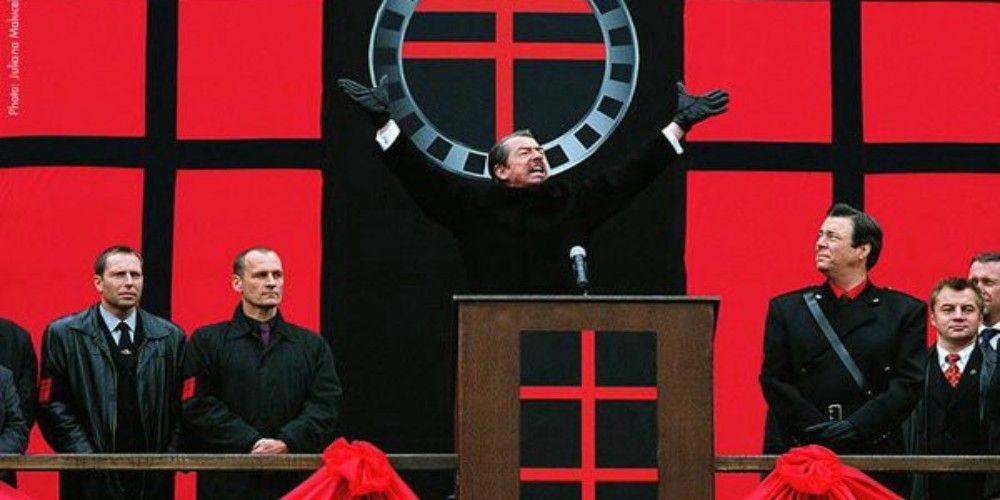

7 WORSE: CHANCELLOR SUTLER AND NORSEFIRE

When depicting fascism in his graphic novel, Moore didn't paint it with a broad stroke. He chose to make Chancellor Adam Susan a nationalist who actively thought he was doing what was best for his country, and that Norsefire and all those who followed it were morally correct and justified.

The Wachowski's made Chancellor Sutler a shrieking jumbotron, a giant talking head spouting devious lies until his mouth foamed up. John Hurt portrayed the character masterfully given he was mostly on a large screen, but the character was two-dimensional, and evil enough the audience would never seriously consider his side just.

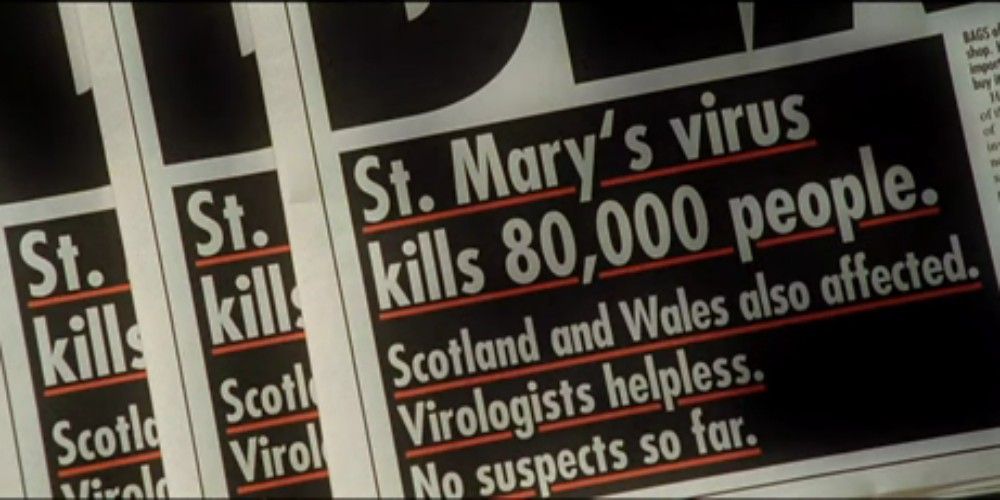

6 BETTER: BIOLOGICAL WARFARE

Though the graphic novel was written in the '80s, it depicts a dystopian future of England in 1997. Its plot is a critique of the views of the conservative party in power at that time, led by Margaret Thatcher. Nuclear war has engulfed the country, and Noresfire has risen to power with Thatcher-like notions of decentralized unions and de-regulation of government.

The Wachowski's set their film in 2020 and focused keenly on Norsefire being responsible for releasing a brutal virus on its own party members as a means to test a biological weapon. Nuclear warfare seems far less likely than a powerful virus strain sweeping an unsuspecting country.

5 WORSE: AMERICANIZATION

Alan Moore's story is inherently British, and he purposefully set it in England to focus his commentary on what was happening politically in the '80s when he wrote it. When the film veered away from that, he chose to distance himself from it on the basis that it was no longer recognizable as his work.

The film is Americanized in a variety of ways, such as focusing on Fingermen spying on citizens (a reflection of the Patriot Act ratified by the Bush administration), as well as shoe-horning a detective mystery into the middle with Inspector Finch's character, who is not as prominent a character in the graphic novel.

4 BETTER: ROMANCE

Suffice it to say there were no whiffs of romance in Alan Moore's dystopian comic, especially not between V and Evey Hammond. V assumed the rule of a strict mentor, and even the relationship that Evey had with Dietrich, a crime boss, was solely for the purpose of survival.

In the film romance underscores much of the plot, and not only helps to humanize V but gives his revenge quest a more altruistic purpose. Love is shown between V and Evey, as well as another important couple, to demonstrate that in order for V to succeed, it isn't enough to fight against a totalitarian government if you aren't also fighting for a better future for those you love.

3 WORSE: CONCEPT OF ANARCHY

The graphic novel has a very specific concept of anarchy, as curated by Alan Moore. He felt that anarchy was about taking personal accountability, and less about a chaotic mob mentality. He believed a government should be held accountable by its people.

The film posits that anarchy is a disruption of the status quo, and almost an inevitability if enough people get fed up with the way things are. Anarchy was also slowly changed in the film to represent simply liberalism, versus Norsefire's neo-conservatism.

2 BETTER: PUBLIC INVOLVEMENT

V primarily worked alone in the graphic novel, save for his accomplice Evey Hammond. He didn't exactly become an inspirational figure for the vox populi, and single-mindedly pursued his goal for his own extremist end, with Moore devoting little attention to the mounting crusade the public was waging.

By contrast, the film explores all the ways that V's message reaches the London population, as various citizens are emboldened thanks to his actions. This is most prominent in the march on Parliament at the end, where almost all of London dons Guy Fawkes masks and appears to confront Chancellor Sutler's troops, which creates a much more inspirational moment.

1 WORSE: INSPECTOR FINCH

As one of the most prominent characters in the graphic novel besides V and Evey, Inspector Finch is vital to the story, but not as the sympathetic government lackey he's portrayed as in the film. He takes LSD to get through the rigors of his job and has no struggling conscience when he shoots V at the end.

The film version of Finch is sadly reduced to a trope of the hard-boiled detective, used mainly for exposition for the audience to follow the events of the narrative as he investigates V's crimes. He isn't made as complex or as interesting as in the graphic novel and is aware of the government's corruption early on.

from ScreenRant - Feed https://ift.tt/37xntzh

No comments: