The Mauritanian tells the true story of Mohamedou Ould Slahi, but mostly skips from Slahi's trial to the present day, leaving some lingering questions about what happened in the intervening decade and what is still to come. Some of these questions can be answered through Slahi's book, Guantanamo Diary, which was one of the sources for the film, and the subsequent event in his life. Others remain to be answered because of the still-ongoing legal debate around Guantanamo Bay and the detainees there.

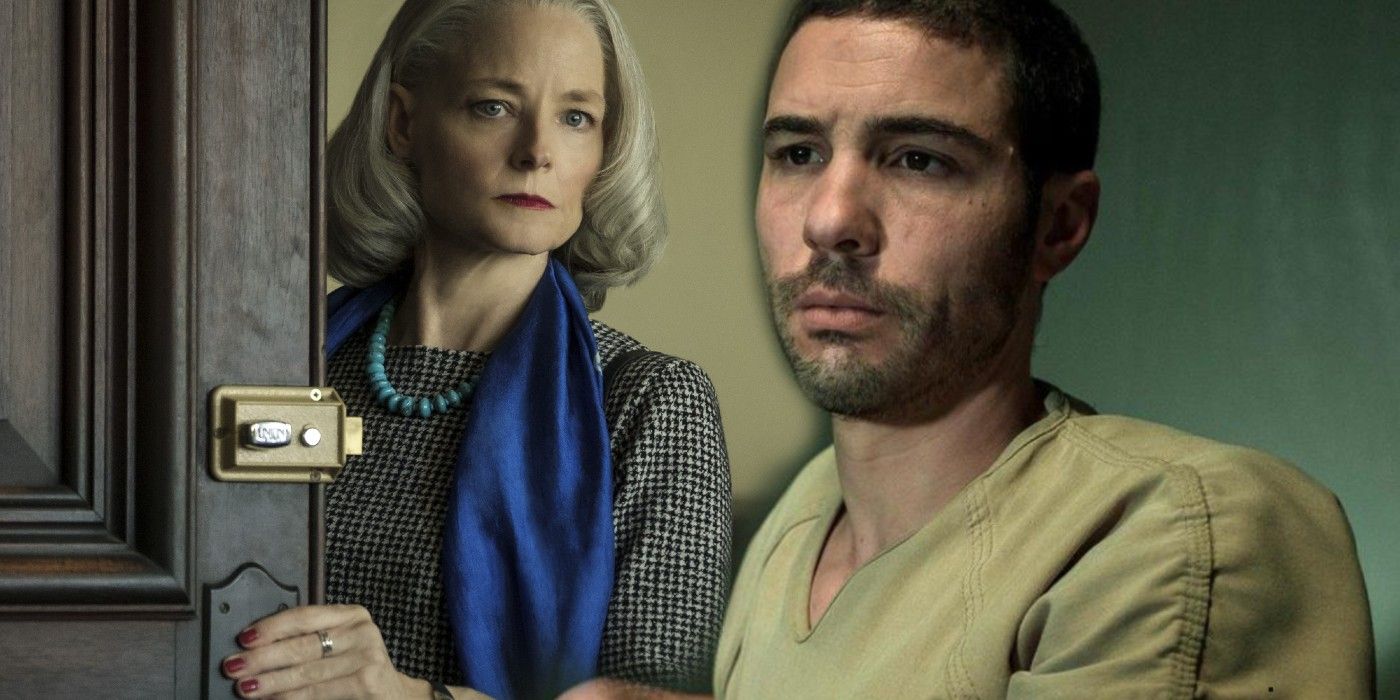

Slahi was arrested in Mauritania in 2001 and was held in an "extraordinary rendition" site in Jordan and then in Guantanamo Bay for almost fifteen years. The Mauritanian tells the story of his experience and the legal effort to free him, lead by Nancy Hollander, portrayed by Jodie Foster.

The Mauritanian simplifies the chronology of the legal battle over Slahi's story to create a more compelling narrative. In reality, Stuart Crouch (portrayed in the movie by Benedict Cumberbatch) refused to prosecute the case in 2003, while the judge did not make a ruling until 2010. The following decade is only covered in the film through a series of captions at the end of the film, leaving out much of the legal struggle to release Slahi.

While The Mauritanian is a fictionalized depiction of Slahi's ordeal, the story follows Slahi's autobiographical account closely, and as such the lingering questions about The Mauritanian are largely the lingering questions about his real-life experience. Like other biopics, The Mauritanian makes choices as to what to include and what to omit. While some questions will only be answered by the passage of time, others are a matter of recent historical record.

The Mauritanian largely concludes with Judge James Robertson granting a writ of habeas corpus. The judge determined that Slahi's past association with members of al-Qaeda and confessions extracted by torture were not enough to hold him, and ordered his release. However, it would still take six years for him to be released.

The US Department of Justice appealed Robertson's decision. In the fall of 2010, the DC Circuit Court of Appeals vacated the decision and returned it to the District Court, asking it to further question Slahi about his relationship to al-Qaeda. However, these hearings never took place. Slahi thus found himself in a kind of legal limbo, not officially released, but not charged or convicted of anything either.

The Obama administration and the DoJ continued to block Slahi's release. While Obama was elected on a promise to close the Guantanamo Bay internment camp, he was unwilling to release people that military intelligence still believed were linked to the 9/11 attacks. Obama had planned to keep some Guantanamo detainees under indefinite detention in US-based prisons, fulfilling his promise in letter if not in spirit, but no US facility was willing to hold accused terrorists.

The Department of Justice under Eric Holder further denied an ACLU petition for a review into Slahi's detention in 2015. The Mauritanian notes that Hollander and her assistant Teri Duncan, the basis of Shailene Woodley's character in The Mauritanian, continued to visit Slahi on a bimonthly basis, but he still endured extreme isolation and was still in the camp during the death of his mother in 2011, a year after his release. A Periodic Review Board finally approved Slahi's release in July 2016, and he was returned to Mauritania in October of that year.

There is a fairly brief account of Slahi's post-Guantanamo life in The Mauritanian, mostly taking place as a montage over the concluding credits. The montage shows Slahi with his family and counting the different translations of Guantanamo Diary. Understandably, such a short segment can't capture the full experience of Slahi's life in the over four years since his release. It's not surprising for movies based on memoirs, like the recent Hillbilly Elegy, to make changes, adding a narrative conclusion to a still-ongoing life.

In The Mauritanian Hollander comments that Slahi should become a writer, and this is what he ended up doing. He originally wrote Guantanamo Diary, a memoir of his experience, in 2005, but it took a decade to be published due to the US government marking it as classified information. Slahi eventually published Guantanamo Diary in 2015 with numerous redactions. Slahi has said that he wrote four more books while imprisoned, but his drafts were seized before his release.

RELATED: Why Amazon Original Shows Now Rival Netflix

Slahi has also made a few public appearances since his release. In 2017, he was interviewed by 60 Minutes, where he expressed forgiveness to those involved in his detention. In 2018 he followed through on this by having a public reunion with Steve Wood, one of his guards at Guantanamo. Slahi also signed a public letter in the New York Review of Books earlier this year urging the newly-inaugurated President Biden to close the Guantanamo Bay prison camp.

Sadly, Slahi's life is still restricted because of his experience in Guantanamo Bay. The United States never returned his passport to him, meaning that he cannot leave Mauritania. This has resulted in him being separated from his wife, another lawyer who worked on his case, and their son. Slahi is also unable to travel abroad to receive treatment for his medical conditions. Even four years after being freed, the impact of his detention remains.

While Slahi may have been freed, the detention center at Guantanamo Bay is still in operation. As depicted in other War on Terror dramas like The Report, the revelation of civil rights violations did not lead to immediate change. President Obama pledged to close the camps, and made an effort to provide a trial to the inmates suspected of terrorism, but ran into obstacles due to the poor organization of the camp's files, the reluctance of stateside prisons to take detainees, and the extensive use of torture at the camp making detainee statements inadmissible in court. The United States military establishment remained certain that the people imprisoned were involved with terrorism, but feared going to a trial due to the taint of torture.

Republican lawmakers still largely support the camp. In 2012, the Republican-controlled Senate voted to prevent Guantanamo Bay detainees from being transferred to the US. President Trump publicly supported the indefinite detention program and, in 2018 signed an executive order for the camp to remain open. While mainstream media may have moved beyond the War on Terror-era paranoia of shows like 24, a large number of politicians still prioritize protection from real or imagined terrorism over Constitutional rights. The ACLU and other civil rights organizations criticized Obama, Trump, and Congress alike for allowing the camps to remain open.

The number of prisoners at Guantanamo Bay has been reduced since the end of the Bush administration, due to releases like Slahi's, but 40 men are still held in the camp. President Biden has announced his intentions to close the internment camp, but many are skeptical after Obama's failure to deliver on the same promise. For now, the fate of Guantanamo and the people within remains undetermined.

Much of the American debate about the War on Terror and the civil rights violations of the Bush presidency has taken place through movies, from early examples like Jarhead to controversial hits like Zero Dark Thirty. The Mauritanian is part of this tradition, ultimately making a strong case that Slahi was a victim of a government willing to ignore liberty in the name of security. The movie concludes by noting that no United States agency has provided an apology to Slahi or other victims of torture, let alone compensation of the kind other countries have given to the victims of indefinite detention. Given the difficulties Slahi had even obtaining his release, it seems sadly unlikely that there will be official redress for what he suffered any time soon.

from ScreenRant - Feed https://ift.tt/3vhScwY

No comments: